By Christopher Clark

Each time I drive into the vast, burning expanse of the Kalahari, leaving nothing but a trail of dust in my wake as the road cuts straight through like a dagger, part of me feels as if I am heading towards the end of the earth.

Or maybe it’s the beginning. I can never figure out which.

Either way, I don’t think I have ever been anywhere that makes me feel so far from ‘home’; from that little island called Britain where almost every empty scrap of land is remorselessly being chewed up by the great cow of urbanisation.

You won’t see many cows in the Kalahari.

When I finally arrived at the gates of Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park after an overnight haul from Cape Town, it was a little hard to believe that anything had ever lived there. Stretching over 3.5 million hectares, this arid piece of land – crossing the border between South Africa and Botswana – is double the size of the South Africa’s famous Kruger National Park and almost the same size as the Netherlands.

When I finally arrived at the gates of Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park after an overnight haul from Cape Town, it was a little hard to believe that anything had ever lived there. Stretching over 3.5 million hectares, this arid piece of land – crossing the border between South Africa and Botswana – is double the size of the South Africa’s famous Kruger National Park and almost the same size as the Netherlands.

The first thing most visitors to the park notice is the appearance of total and overpowering silence. But hidden beneath the silence, I would soon discover that a rich and complex ecosystem and indigenous culture continues, against the odds, to survive and adapt to the changing world around them.

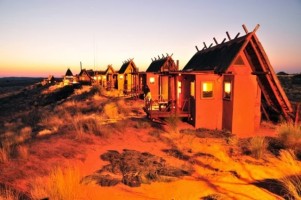

Once inside the park, I drove straight through to !Xaus Lodge, the park’s only fully-catered lodge. The twelve wooden chalets and luxurious main reception area all look down onto large herds of springbok and wildebeest grazing quietly on the plains below, which skirt a large heart-shaped salt pan (!Xaus means heart in the language of the Nama tribe).

I quickly got the feeling that when the lodge was built a concerted effort was made to alter the area as little as possible. Dotted discreetly across a small hillock, the whole place blends seamlessly into the desert and dunes around it. The lodge is unfenced, and even the purified drinking water found in the chalets comes from local desert springs.

When I awoke after an early first night, the roar of lions marking their territory punctuated the cool, hazy morning stillness; otherwise there wasn’t a sound. As I walked from my cabin down to breakfast, I could see fresh lion tracks in the sand just off the wooden walkways. There are more than 450 lions dwelling within the park.

But more than the wildlife, what had really drawn me to Kgalagadi was the search for the indigenous San people who have called this landscape their home for tens of thousands of years. Their adept desert lifestyle and intimate relationship with the ecosystem around them existed long before any other humans had set foot in this part of Africa.

However, over the last few centuries the fate of the Kalahari San has not been a particularly happy one. With the arrival of European settlers and explorers in the 16th and 17th centuries, land was gradually carved up into freehold farms, which had severe implications for the hunter-gatherer lifestyle of the San, who were displaced onto ever diminishing tracts of communal land and found it increasingly difficult to find adequate resources to sustain themselves.

However, over the last few centuries the fate of the Kalahari San has not been a particularly happy one. With the arrival of European settlers and explorers in the 16th and 17th centuries, land was gradually carved up into freehold farms, which had severe implications for the hunter-gatherer lifestyle of the San, who were displaced onto ever diminishing tracts of communal land and found it increasingly difficult to find adequate resources to sustain themselves.

At the same time, the San were often fatally susceptible to diseases that arrived with the Europeans and their livestock, and they were also victims of violent genocidal acts (it was possible to get a permit to hunt San ‘bushmen’ until 1927). So it was that by the early decades of the 20th century, the vast majority of the San had been wiped out.

When the Kalahari Gemsbok National Park was established in 1931, the livelihoods and freedom of movement of some of South Africa’s last remaining first peoples, most notably a clan called the ‡Khomani, were curtailed. Some people were resettled at the national park headquarters at Twee Rivieren, and some gained employment with South Africa National Parks. Many others, however, having been dispossessed of their land, dispersed into Namibia, onto nearby farms and further afield.

A similar fate was also thrust upon the Mier, a community who originated from the mixed race descendants of white landowners and Asian or African slaves. These so-called ‘bastards’ had fled the Cape in search of freedom and had come to call the Kgalagadi region their home in the 1870s only to then be cast out along with the San.

But in May 2002, after a lengthy appeal process that started seven years previously in the aftermath of apartheid, the ‡Khomani, San and the Mier reached a historic agreement with the government of South Africa and South African National Parks, which would return 50,000 hectares of their cherished earth to the tribes.

Having finally won back their land in what today is known as the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, the ‡Khomani and Mier communities then leased the land back to South Africa National Parks. Funds for the construction of !Xaus Lodge also formed part of the agreement, with the ‡Khomani and the Mier again being awarded ownership of the facility. The lodge is now managed on their behalf by Transfrontier Parks Destinations, a consortium of social entrepreneurs who are committed to responsible tourism and ensuring that tourist ventures in particular areas are an asset to local and indigenous communities first and foremost.

The ‡Khomani and Mier not only receive a monthly rental payment from the lodge’s turnover, but most of the lodge’s staff are also recruited from the very same local communities, where previously, having been forced to abandon not only their land but their very way of life, unemployment and social issues like alcoholism, domestic violence and drug abuse were rife.

The ‡Khomani and Mier not only receive a monthly rental payment from the lodge’s turnover, but most of the lodge’s staff are also recruited from the very same local communities, where previously, having been forced to abandon not only their land but their very way of life, unemployment and social issues like alcoholism, domestic violence and drug abuse were rife.

After having my breakfast, I accompanied some of the local San on their regular morning outing, tracking silently through the desert, the history of survival in this harsh environment etched into the accentuated lines on their faces.

Back at the lodge in the afternoon, I sat with some of the local San people as they crafted traditional wares and artifacts that would be sold in the !Xaus gift shop or used to decorate the chalets. Sitting around a fire once dusk had fallen, some of the ‡Khomani then shared stories of their sacred and revered wild animals, and the founding myths of the great sky and canopy of stars above us.

But for all their knowledge of their history, these San, dressed in modern clothes, were not here to serve as a living museum. They did not seem to be yearning for a sepia-like, romanticised past – the kind of past that tourists still too often wish to see. They had astutely taken the opportunity to move with the times, marrying the demands, expectations and trends of the 21st century with their long attachment to the land beneath their feet. And with a helping hand, they were doing it their way. For the most part, it seemed to be working too.

As the evening drew on, I realized that something important was happening there in the Kgalagadi. The close triumvirate that had been formed between Transfrontier Park Destinations, !Xaus Lodge and a group of South Africa’s first inhabitants showed clearly that it was possible to balance a region’s rich cultural heritage, environment and ecosystem, and a growing influx of tourism in a way that is mutually beneficial to all. And it felt good to be a part of this picture for a moment, whether it really was the end of something, or merely the beginning.

In the Kalahari I can never seem to figure out which is which.

About the Writer

About the Writer

Christopher Clark is a British freelance journalist based in Cape Town. After travelling to more than 50 countries worldwide, he came to Africa on a wing, a prayer and a one way ticket in 2008. He writes for various platforms including Africa Geographic, News24 and Future Challenges and was featured as one of The Big Issue’s best young writers in South Africa in 2012. www.cawclark.com