It was a perfect day, the kind where the sun glimmers and slowly glides across an impossibly blue sky and the warm wind gently kisses your face as it passes by. Princeton was just beginning to quiet down for the summer as the last bunch of students began to trickle out of town and residents scooted off to summer homes and two-week holidays.

As I approached the corner, I watched the boulanger as he made his way down to the freezer and disappeared underground. On any other day I would have strolled by the bakery, reveling in the scent of freshly baked bread wafting through the air and maybe even paused to take a peek at the old-fashioned shelves lined with beautifully rustic baguettes, boule and ciabatta before heading to my destination, but today I followed the scent inside.

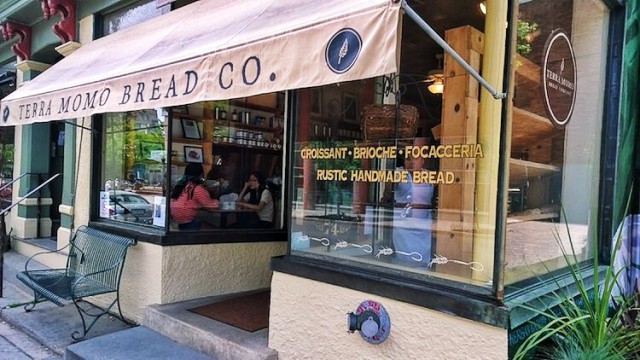

I had been to the Terra Momo Bread Company many times before, often grabbing a slice of Roman style pizza (just like my Nana used to make) or a couple of chocolate-filled brioche, but rarely for a whole loaf of bread. In fact, over the past three years I slowly began taking wheat out of my diet. It was not something I enjoyed, but rather a health choice I had made as a result of the many ominous warnings pertaining to the negative effects of gluten.

The light to this very dark food restriction tunnel came when I learned that sourdough — traditionally made with a long fermentation process and wild yeast – might actually be safe for consumption and better yet, healthful. This kind of bread hosts a symbiotic culture of bacteria (lactobacilli) and airborne fungus (wild yeast) in which each element within the relationship provides something the other elements need. The wild yeast creates enzymes that break down the carbohydrates, phytic acid and gluten, which are then ‘eaten’ by the good bacteria. The process creates lactic acid, which contributes to better digestibility of the bread. Most people consume commercial breads, which are made with baker’s yeast and are usually prepared and baked within three hours, as opposed to the 24-hour fermentation process that occurs with traditional sourdough.

I was meeting Denis Granarolo, the boulanger behind the artisan breads, pastries and cakes at the bakery to try some of his pain au levin, the French term for traditional sourdough. A few weeks before, I learned that Granarolo was one of the few bakers in the country to use wild yeast and long fermentation to produce his pain au levin. It felt good to know that this art of bread making was still alive and that I had access to it within minutes of my home.

Granarolo, a slim man with a beautiful thick French accent spoke with excitement about his breads as he gave me a tour through the bakery and underground freezer. The boulanger started his career in France after opening his first bakery in 1983. Ten years later he came to America and opened the Witherspoon Bread Company (the former name of the bakery) with the Momo brothers, owners of the Terra Momo Restaurant Group. Ever since then his day begins around 2:00 a.m. and ends at 8:00 a.m. when the day’s bread is baked and on the shelves. All the the pastry preparation is done during the day due to space constraints, but it is obvious from Granarolo’s extensive knowledge and passion that he has his hand in every aspect of the production process.

As we walked through the freezer and around a large table dusted with flour and all the necessary ingredients to make chocolate croissants, he offered small lessons on each of his different varieties of bread – from baguettes to huge round loaves of rye-based rustic sourdough – explaining that he uses a more traditional production process for all of his breads, which are all produced with non-GMO flour. While most commercial breads are done in a few hours, all of Granarolo’s breads go through a four to five-hour fermentation process.

A large part of the reason why Granarolo wanted to work with the Momo brothers was because they, like him, value slow food. He told me that in France many bakeries are resorting to commercial bread making to lower their costs and increase production. Granarolo wanted no part of that, so he works tirelessly in his 1,000 sq. ft. space to replicate the artisan baked goods of his childhood. “I even tried to make a bread with longer fermentation — two, three days — but I just did not have the space to do it,” he tells me.

As if he could sense my excitement, Granarolo saved his pain au levin for last. The boulanger shared that this bread was his favorite — a masterpiece of sorts carrying time-honored methods of long ago. He grabbed a loaf off the shelf with bare hands and effortlessly sliced it in half with a knife, revealing airy pockets of soft bread. Ripping off a piece with his fingers, Granarolo bit off a chunk of the perfect bread holding the remaining piece in the air as he proclaimed, “I love this bread.”

I watched quietly behind my camera as this man, who had spent most of his life dedicated to preserving an ancient art, enjoyed the fruits of his labor. And I, for all the joy I felt at that moment, selfishly couldn’t wait until I too could sink my teeth into Granarolo’s perfect pain au levin.

All photos taken with our Lumia Icon