By Deja Dragovic

I just read this investigative report in The New York Times, a gripping expose on New York City’s nail salons. It directly addresses labour exploitation, modern slavery, human rights, illegal migration, the polarization of power, inequality, xenophobia and racial discrimination.

Indirectly, it also raises questions about consumerism, the value of services and commodities, and morality, which, in keeping with the topics of my blog, is what I am interested in elaborating on at present.

But how does an individual decision to have a $10-manicure matter, in the grand scheme of things?

Modern forms of ‘slavery’ are present in construction, agriculture, hospitality, and basically across all industries; it is not specific to beauty and fashion. The social system in which we exist is massively exploitative. And, regrettably, it is an inevitable link in the consumerist chain.

In general, our society operates on the basis that those less fortunate, less privileged, less resourceful, or less able are being exploited. The well-off at the top of the pyramid do not have to produce anything, they do, however, actively participate in the distribution of goods (by spending, which is essential to its triumph as such, and by parading this apparent affluence).

By practicing and participating in consumerist activities, we are purchasing products and services, creating a demand for them, and are, thus, inadvertently supporting and perpetuating the system because, in order for a product to be made cheaply, or a service to be provided cheaply, someone, somewhere down the line has to be underhanded, underpaid or overworked.

Value analysis

Difficult economic situations force the residents in less developed countries or those from the less fortunate communities or backgrounds to seek alternatives: despair or the lack of options often cause people to take on work in which they are subjected to grueling conditions, difficult terms, and harassment, even in advanced societies which have strict laws recognizing basic human rights.

The same principles can be applied to cheap ‘high street fashions’ manufactured in sweatshops in China, Bangladesh, etc, employing children who are paid less than a $1/day so that Primark can sell outfits with a £2 price tag. Those items are flying off the shelves.

The demand exists because everyone wants a bargain, but mainly because those using the service or purchasing the goods largely do not question how someone can afford to provide a $10 manicure or make a £2 dress.

Also, the same can be said for other services. Why can, for example, writing projects on Elance (a freelancing website) be allocated at $2 per 1000 words? Who agrees to that fee? Well, for one, $2 is not the same everywhere.

Got off topic a bit here, but the point is that what needs to get done finds a way of getting done because, for lack of any other opportunities, these are jobs after all, and there will always be someone who will do it because it will still be marginally better than nothing.

Exploitation

This isn’t the first report of this kind, and certainly not the first to call attention to the serious violations of labor, the exploitation of people, illegal wages and poor living conditions.. One of the more notorious exposés is Santa’s Workshop: Inside China’s Slave Labour Toy Factories, which revealed that there are more than 200 million children unjustly employed around the world. They have no access to education and are not given any other choice but to work in factories. It is safe to say that they may not even be aware of any other options. Traffickers lure millions of children away from their families, and millions of them are born in debt bondage, or forced to work as slaves. Because there’s demand for the items they are employed to produce.

The Western society’s unquenchable consumerist thirst, particularly intensified during the holidays, keeping the culture of gift exchange thriving, creates a relentless pressure on outsourced suppliers to deliver products at low costs. For example, the majority of chocolate products on the market, up to 70 percent globally, comes from the plantations of the Ivory Coast, which employ children as young as the age of 5, children who are usually abducted or sold to labor by their own families.

Demand

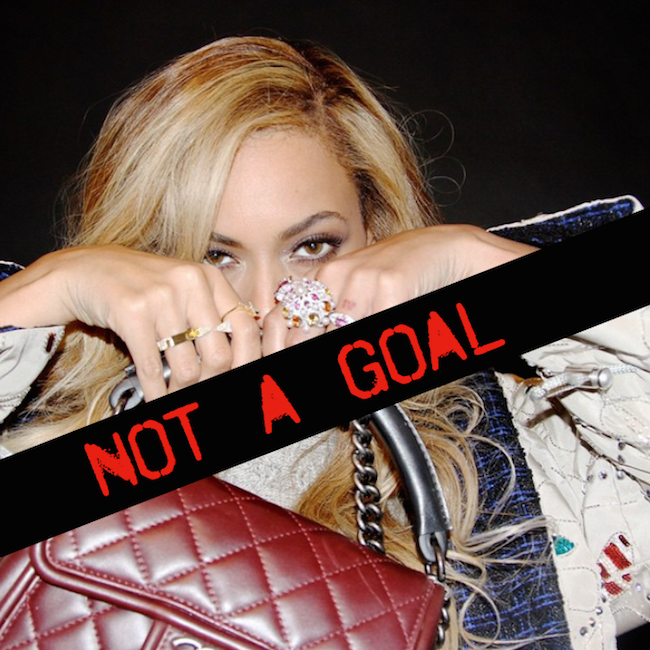

Why do we keep acquiring products, clothes and gadgets that we don’t need? Is it so that we don’t feel like less in the eyes of society? Or so that we can be admired for the things that we own and the way we look?

Wherever we go and whatever we do, it is increasingly hard to escape the forced mentality (by way of aggressive advertising) that we need to spend more as a way of life which promises to raise our appeal, desirability, success, and social influence and reputation. This need for constant purchasing and spending and the accumulation of goods comes from the need for security. Historically, those who accumulated things did it for survival, for example through the winter when food and firewood became scarce. But in the contemporary world, there is no need for that any more – the advances in civilization brought us all the required safety.

So what are our reasons now? What are these feelings of insecurity rooted in? :in our psychological need for dominance, influence, competence, belonging, solidarity, etc. People who seek solace in materialistic things often feel that what they have is not enough. As it takes a lot more time and effort to deal with and attend to psychological shortfalls, consumers are conditioned to believe that ‘retail therapy’ is a viable solution. A perfect manicure in a vibrant, glossy colour has become a means of dealing with difficult situations. Spending money has become a socially approved means of counteracting dissatisfaction…

More on that in the upcoming Materialism: the psychology of spending post.

Lastly, are these statistics enough to convince us that we as consumers are responsible for those circumstances?

Do not underestimate the power of individual choice or action. If each of us purposely does not go ahead with the next purchase of whatever frivolous item on the wishlist, if each of us boycotts products and services for which a being has suffered or was treated unfairly – for our cuticles, our fur or our meal – would that not trickle through collective humanity and eventually change the entire system? It might take a while because, instead of preventing such circumstances we now have to reinstate normality, but it is possible. Moreover, it’s necessary.

But if you can still be indifferent after being given this information, if you still keep your habits, what are your reasons?

This article was originally published on a rebel with a cause