By Jessica Colarossi

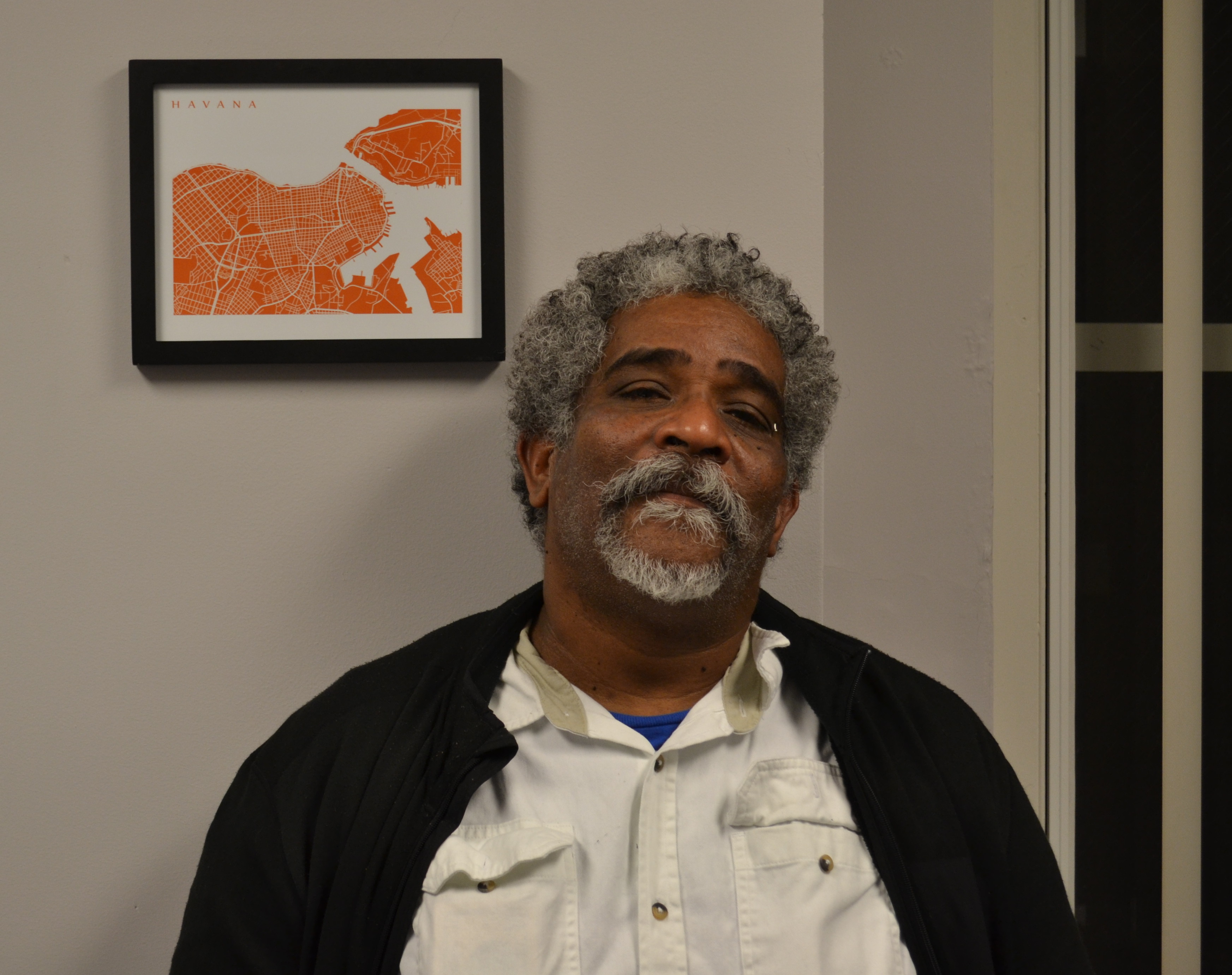

Last year, Cuba got its first-ever queer studies course. About a half dozen adult students read texts about queer theory and Cuban literature and analyzed paintings and music in the back of a book shop in Havana. The course was small but promising. Leading it were two of the most important intellectuals in this island nation: Victor Fowler Calzada, a poet and essayist, and his friend Norge Espinosa Mendoza, also a poet and essayist, as well as an actor and playwright. The two men hope to continue teaching when Fowler Calzada returns to his country in May. In the meantime, he is on a year-long fellowship at Harvard’s W. E. B. Du Bois Research Institute in Cambridge, Mass., studying Cuba’s role in African-American intellectual history and writing his sixth book of essays about the “Cuban revolution of a field of cultural wars” in Cuban diaspora literature.

Fowler Calzada is a changemaker in every sense of the word. Born in 1960 to an Afro-Cuban family and originally trained as a teacher, he began writing poetry in the 1980s. He said he’s influenced by many writers around the world, including Charles Bukowski, Walt Whitman, James Joyce and Franz Kafka. His poetry touches on his perception of Cuba and experiences within and outside his country, while his essays dissect race relations, gay rights and much more. He is the author of 10 books of poetry and five books of essays and winner of top literary prizes in Cuba.

Katerina Gonzalez Seligmann, a friend and colleague of Fowler Calzada and an assistant professor at Emerson College in Boston, brought the writer to her campus for a reading in February, hoping he could shine a light on life in Cuba for students and faculty and open further dialogues about Latin American literature. “There are many ways in which his work will be unexpected,” she said. “It’s not going to fall into a neat, easy reading, and Victor is of a highly complex mind.” One of the poems from his most recent book of poetry, “Conversations in Havana,” Gonzalez Seligmann explained, is about “mourning friends losing their lives and having to survive that.” Another, she said, about a man with no legs, called “Without Enchantment,” addresses the “heroism of disability and walks a very fine line of admiration and curiosity about enduring difficulties in life.” A poem called “Let My Children Sleep,” according to Gonzalez Seligmann, is about a “general unease that he wishes is not carried over to his children.”

When Fowler Calzada arrived at Emerson’s Writing, Literature & Publishing Department, he was greeted with handshakes and admiration from fellow teachers. Fowler Calzada took his time with introductions while making his way to Gonzalez Seligmann’s office. Once there, he took note of the books on the shelf; the cartoon drawing of Havana, Cuba, hanging on the white wall behind her desk pleased him.

“Ahhhhh,” he sighed, thinking deeply about his writing and experience as an educator. He sat on the other side of Gonzalez Seligmann’s desk, rubbing his gray, tight-wound curly hair. Observing the room, his expression was relaxed, an eyebrow piercing over his left eye. “This is what I do when I think,” he said with a soft smile and a thick Cuban accent. “The most important influence [in writing] is life, of course.

“It’s an art, no? I believe writers in all the ages in one way or the other, in all the countries, they have one moment with the same question: How do I express all that I have in my mind? How to put this into words? How to represent reality, dreams, how to speak for myself, and how do I speak for others, too,” he explained.

Fowler Calzada’s areas of focus spread widely, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual and transexual rights; racial justice; and U.S.-Cuban political relations. Gonzalez Seligmann also explained that Fowler Calzada regularly edits volumes for Cuban libraries and books he wants to make sure are available for ordinary Cubans, calling him a kind of “disseminator of thought in Cuba.” Fowler Calzada wants to provide students with the ability to question and the tools to act.

Education has been Fowler Calzada’s primary contribution to social change in a country whose system is vastly different than the U.S. Cuba esteems itself on having some of the highest-ranking universities in the world.

“Education is a process of dialogue between the knowledge of humanity, between the particular situation in the place you are in, and who the student is. If the student pays attention, you are also learning at the same time. In that sense, teaching is identical in every country,” he said. “I don’t want to offer an answer to all the problems, because there are many problems we face that I don’t have an answer. But what I want my student is [to] get the desire to make the questions, the unconformity, that is what’s important to me.”

Fowler Calzada has lectured at universities across the United States, including Princeton and Brown. He and Gonzalez Seligmann have also taught many study-abroad programs and have worked together professionally since Gonzalez Seligmann’s first research trip to Cuba in 2009. She received her doctorate in comparative literature from Brown University and began teaching Latin American Literature at Emerson College this past fall. The two also worked together in 2012 at a summer program in Cuba where Gonzalez Seligmann taught a literature course and Fowler Calzada taught a film course.

“Teaching American students is very difficult,” he said with a laugh. “We have a lot of differences in our countries, but we need both to learn how to see the other in different ways.” He tries to show the complexities of the Cuban experience to students when he teaches, he explained.

Fowler Calzada spoke to a room of over 50 Emerson students and faculty. He read his poems in Spanish, and Gonzalez Seligmann followed each poem with an English translation. The room was silent, intently listening to the pace of his breath, captivated by his animated storytelling. He read 20 poems stretching across realms of his experience and perspectives, from the death of his father, to a wall on the shore of Cuba, to a poem about poetry. The final two poems he translated to English himself. When he spoke the last word of the poem, the room exploded into applause.

His outlook on life is a refreshing one; truly believing in the goodness of people and their desire to create change. He encourages this type of learning to his students and his own three children who live in Cuba with his wife. Education will not “totally transform” a person, he explained, but “it is difficult, maybe impossible, to find someone to whom you ask, ‘Do you want to help humanity? Do you want to better the world?’ who says, ‘No.’

“Education is a mystery,” Fowler Calzada said. “You could create change, no? You could,” he said to me.

“Yes,” I replied. “I suppose I could.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jessica Colarossi is working on her B.A. in journalism and minoring in publishing at Emerson College. She previously interned at ThinkProgress and has also written for other campus publications covering music, health, sustainability and local news. Jessica is originally from Lindenhurst, New York. Follow her @heyitsjessc.

Photographs of Victor Fowler Calzada and Katerina Gonzalez Seligmann by Jessica Colarossi