By : Kristen Lee Cronon

Ankle-deep in the soft sand of the Anchicayá River, Jose points to where his coca farm used to be: atop the green mountain that rises above us like a fortress of moss-covered vines and palm fronds. To get there, you swim across the river and hike up to his jungle plot where spider monkeys and umbrellabirds congregate.

Two years ago, Jose signed an agreement with the Colombian government that he would destroy his coca plants, the raw material used to produce cocaine, in exchange for subsidies to help ease the transition to other crops. Jose and his neighbors eradicated the coca crops they had relied on for decades, but the subsidies have not come through as promised—putting Anchicayá’s rural economy under strain.

In need of new foundations for their local economy, community members searched for solutions in surprising places: in the conservation of the region’s forests, rivers, birds, and frogs. I spent a day in Anchicayá with Jose, now a local guide with the community-run ecotourism organization, Cortucan. We wound our way through the lush valley on motorcycle, stopping to explore swimming holes, waterfalls, and birding spots, as we talked about the question: what’s next for Anchicayá’s remote rural economy that has historically relied on coca? Could ecotourism help give momentum to the local economy and conservation efforts alike?

From cloud forest to tropical rainforest

With the mountainous Los Farallones National Park on one side of the river, and the Anchicayá River National Protected Forest Reserve on the other, the Anchicayá River Valley boasts an astounding range of ecosystems. To get there, you head to the sleepy mountain town of El Queremal and descend the old dirt road towards Colombia’s Pacific coast, passing from the wispy fog and sweater weather of the cloud forest, dense with tall ferns and moss-covered trees, to the sticky tropical heat of the Chocó rainforest.

This remarkable range of environments, each with distinctive flora and fauna, makes the Anchicayá Valley one of Colombia’s biodiversity hotspots, explains Jeisson Zamudio, a bird researcher at Asociación Calidris, a Cali-based research and conservation organization. Asociación Calidris and Cortucan hope to use the valley’s diversity of wildlife—birds in particular—to propel much-needed economic alternatives and conserve the region’s rich biodiversity.

In partnership with The Audubon Society, Asociación Calidris has helped train community members in Anchicayá, and other key birding sites across Colombia, to be local bird guides, with the goal of strengthening grassroots ecotourism and local conservation efforts.

And there is much to conserve. Over 600 species of birds can be spotted in Anchicayá—more than half as many bird species as the United States and Canada combined. Of these species, 20 are endemic to the region, and 70 are endangered. The valley is also home to a vibrant diversity of snakes, monkeys, and frogs, including the endangered endemic species, Lehmann’s poison frog.

Low hanging fruit for guerrilla control

For decades, Anchicayá’s rich biodiversity was nearly inaccessible. Down a winding, rocky dirt road, four hours from the nearest big city, Anchicayá was an easy target for guerrilla groups, the National Liberation Army (ELN) and then later the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Both groups pushed coca production on the region to finance their operations. Anchicayá’s geographic isolation also meant that local farmers had very few economic options.

“The region was abandoned by the state,” explained Freddy Rebolledo Tenorio, co-founder of Cortucan, and one of Jose’s fellow ecotourism guides. “Transportation challenges made it very difficult for people to trade other products, so elicit crops were the most viable option.”

A hectare of coca plants can be processed on the farm into a kilo of cocaine paste, which is a lot easier to transport than a hectare’s worth of bananas—and a lot more lucrative.

Jose remembers that under the ELN, the guerillas kept the region under tight security and the money was decent. But when the FARC showed up to take control, violence escalated. In the first decade of the 2000s, community members were terrorized, forced out, and killed in the crossfire between FARC guerrillas and paramilitary soldiers.

“It was a matanza” said Jose quietly, which means ‘massacre’ in English. Many people had no choice but to abandon their land.

Broken promises on the path to recovery

After decades of guerilla occupation and armed conflict, the 2016 peace treaty between the FARC and the Colombian government brought a newfound feeling of safety to the region—and promised an out for coca farmers. In exchange for voluntarily destroying their coca crops, they were promised three years of subsidies (around $300 USD per month) and technical support to help them transition to other crops.

Jose and his neighbors replaced their coca crops with chontaduro, plantains, bananas, egg-laying chickens, and aquaculture of tilapia and other freshwater fish. But the promised payments and the technical support have either been delayed, or haven’t come through.

“It’s been very slow,” Freddy explains. “We should be in the second phase of the project, but we are still in the beginning stage of achieving food security.”

Farmers throughout Colombia are in the same boat. Many who had eradicated their coca as part of the peace process have since turned back to the illicit crop. In fact, coca cultivation hit an all time high in Colombia in 2017, the year after the treaty was signed, dropping only slightly in 2018.

The Anchicayá community was pressed to find other options to rebuild their rural economy.

Birding takes flight in upper Anchicayá

Just 20 minutes up the road from Jose’s home, cafe owner and bird enthusiast, Dora Londoño, was testing a novel concept for the region and seeing promising results. Dora, inspired by bird researchers who started to show up after the FARC moved out, saw business potential in an unexpected place: the ficus tree behind her home—and the colorful birds that flocked to it.

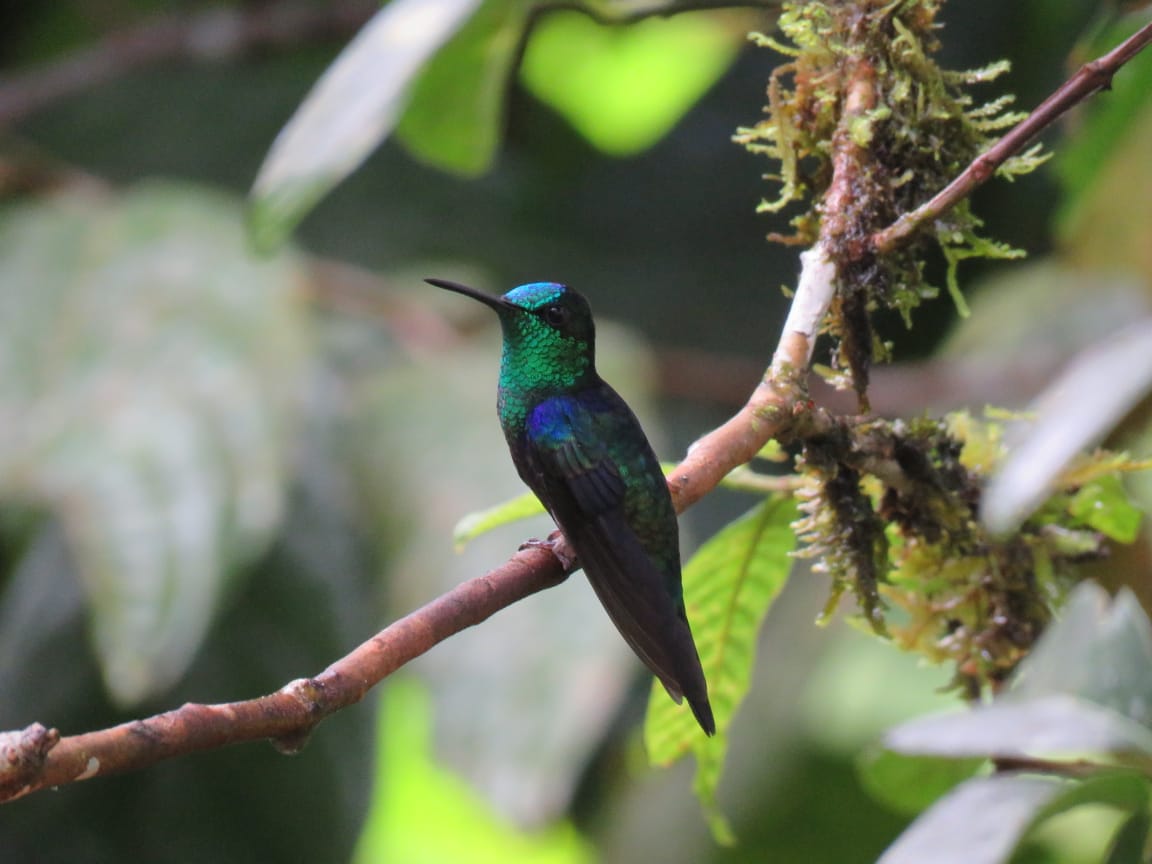

In 2013, Dora began to transform the small storefront she ran out of her home into a birdwatching café, putting out fruit and bird feeders to attract more and more species over time to her already birdy backyard. Of the 500+ species of birds in the region, over 430 can be spotted here, including the Toucan Barbet, Black-chinned Mountain-Tanager, Empress Brilliant, and Speckled Hummingbird.

When Jose and I pulled up on his motorcycle, Dora greeted us in an excited whisper and guided us to the back patio: “Welcome! Go go! Go out back, the Emerald Toucanet is right there!” Sure enough, the lime green-and-blue toucanet was perched on a branch just a meter away, lifting its iridescent head to examine us.

Dora’s son, Gieler, explained that during much of the guerilla occupation, so few people passed through the region that his mother was lucky if a single customer per day stopped by her store. Since then, her café has grown internet-famous in the birding community. It is now considered one of the top birding destinations in southwestern Colombia, offering home-cooked meals and lodging, and attracting birders from across the globe.

Threats to biodiversity accelerate post peace treaty

Birders weren’t the only ones who were quick to take advantage of the reopening of Colombia’s wild regions. After the cease fire, rural regions formerly occupied by guerilla groups became newly accessible for development. Cattle ranching, logging, mining, and African oil palm cultivation took off, marking a sharp acceleration in deforestation in former FARC-controlled regions of Colombia. Illegal industries, like illicit resource extraction and animal trafficking, also expanded.

Anchicayá was no exception. Freddy explained that as the region became safer post-conflict, endemic animals, like the endangered Lehmann’s poison frog and the endemic Toucan Barbet, started to disappear in increasing numbers. Plus, visitors drawn to the Anchicayá river’s cool, green swimming holes, started showing up in increasing numbers—and leaving behind more trash than the community knew what to do with.

“We saw the great need for us to organize as a community,” said Freddy. Tourists were already showing up in the region in an uncontrolled manner, and we needed to create a foundation for sustainable, community-driven ecotourism.” And so they created Cortucan, Anchicayá’s very own community-run ecotourism service and nature reserve, with the mission of creating economic alternatives for locals and supporting the conservation of the region’s wildlife.

Building tools for tourism and conservation

Too often, the environment suffers when “ecotourism” in rural areas takes off in an uncoordinated, unplanned way, explained Dairo Antonio Utima, Cortucan co-founder. According to Dairo, Cortucan was determined not to let this happen. They sought support from National Parks of Colombia, academic institutions, and nonprofits, including Calidris, which had previously trained other rural communities in the region to offer conservation-focused bird tourism. Community members set to work, studying bird-identification, tourism, conservation, and English with Calidris.

“It taught us to fall in love with birds, with the species around us—to get to know them, how important they are, and all that they bring to the region,” Dairo told me.

Calidris and Audubon, with funding from the Critical Ecosystems Partnership Fund and Colombia’s Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism, are working to develop Colombia’s Southwestern Birding Trail, which links Anchicayá with unique birding sites across 46 municipalities. Their vision, shared by social leaders like Freddy and Dairo in Anchicayá, is that local communities, when equipped with the right tools and economic alternatives, could be a vital defense against mounting threats to biodiversity in rural Colombia.

This is why it’s so important that ecotourism is community-run, Dairo explained. “It enables us to generate alternative income for the community, beyond agriculture—allowing us to strengthen [our economy] in a way that minimizes environmental impact. We are able to generate a different culture, focused on conservation.”

Community-run ecotourism takes off in Anchicayá

A decade ago, no one in Anchicayá would have believed that ecotourism, and birding in particular, could ever take off here, Jose told me. Now, the idea is starting to feel more real to people: maybe there could be another viable option besides coca farming. A new option that conserves, instead of degrades, the region’s remarkable biodiversity.

Today, you can bird your way down from Dora’s in the cloud forest at the top of the valley, all the way to the rainforest of Cortucan’s reserve—where ecotourist guides from the community now offer maintained trails, birding, and guided excursions on the river or up into the mountains to see Lehmann’s poison frog.

To ensure the area’s conservation, the community limits the number of visitors and provides a short orientation on how visitors can help take care of the reserve. At first, visitors resisted the change, Jose told me. They didn’t want to pay the entrance fee (equivalent to $2 USD). “So we would tell them they could pay whatever they felt was fair at the end of their visit,” Jose said. “People would often pay more than double the fee we were asking.”

And I can see why. Jose and I pulled up on his motorcycle and followed a well-maintained trail past yucca and banana trees to the sandy riverbanks of the reserve. A lazy emerald river, and the first of seven glassy swimming holes in the reserve, stretch out in front of us. The river is so peaceful and clear, it’s hard to imagine a time when it was flanked by trash—and even harder to imagine it occupied by armed FARC guerillas.

“We’re not interested in crowding this place with tourists,” Jose said, gesturing upriver to green pools and lazy eddies, shaded by leaning rubber trees. “We want to educate visitors and locals on how to take care of it, so that we still have all of this years in the future.”

Kristen L. Cronon is a freelance writer living in Medellin, Colombia.